Intravenous Alpha-Lipoic Acid

This document is intended for informational purposes only and does not provide

medical advice, treatment recommendations or therapeutic claims.

1. INTRODUCTION

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) is a naturally occurring short-chain fatty acid that

serves as a cofactor for several mitochondrial enzyme complexes and participates

in cellular redox cycling. In scientific literature, ALA has been examined for its

biochemical roles in oxidative processes and metabolic pathways.

Intravenous ALA has also been described in research settings as a route of

administration used to characterize its pharmacokinetic behavior and its

disposition under controlled experimental conditions.1–3,9–10

2. CHEMISTRY AND PHYSIOLOGICAL ROLE

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) is present in various tissues, particularly those with high mitochondrial density such as the heart, liver, and kidneys. It is also found in several plant-derived foods, including spinach, broccoli, peas, tomatoes, Brussels sprouts, and rice. Endogenous synthesis occurs within the mitochondria, where ALA is enzymatically derived from octanoic acid.

Dietary intake can contribute additional ALA, although reported bioavailability varies depending on food composition and preparation.9

Chemically, ALA is a five-carbon disulfide-containing compound, also referred to as 1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid or thioctic acid.

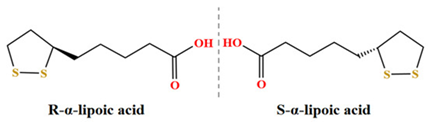

It contains a single chiral center and exists as R- and S-enantiomers, with the R-form representing the naturally occurring configuration (Figure 1).1

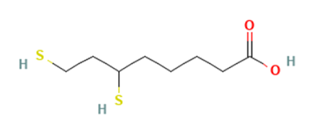

ALA participates in several mitochondrial enzyme complexes involved in oxidative biochemical pathways. Its amphiphilic properties allow distribution into both aqueous and lipid environments, and in vivo ALA can be reduced to dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA), a dithiol form (Figure 2). ALA and DHLA are described in scientific literature as components of cellular redox systems that interact with various electron-transfer processes and metal-binding reactions.⁹

These redox interactions have been studied in relation to broader cellular signaling pathways and metabolic chemistry, without implying specific physiological effects or therapeutic outcomes.1–3,9–10

Figure 1. R and S enantiomers of Lipoic Acid.

Figure 2. 2-d chemical structure of DHLA.

3. PHARMACOLOGY AND MECHANISM OF ACTION

Alpha-lipoic acid and its reduced form, dihydrolipoic acid, are described in

scientific literature as participating in cellular redox cycling. These redox

interactions have been examined in experimental models as part of investigations

into oxidative processes and cellular signaling pathways.

ALA has also been characterized as a component of mitochondrial multienzyme complexes involved in oxidative biochemical reactions. Research has explored potential interactions between ALA-derived redox states and intracellular thiol systems, transcriptional regulators, and metabolic pathways in cell and tissue models. These studies are intended to describe the compound’s biochemical behavior and its role in redox-associated mechanisms.1–3,9–10

4. PHARMACOKINETICS OF INTRAVENOUS LIPOIC ACID

In published studies, intravenously administered alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) has been described as distributing rapidly into tissues and undergoing metabolic transformation predominantly through β-oxidation and conjugation pathways in the liver.3–4 Oral administration of ALA has been associated with variable systemic exposure, whereas intravenous administration has been used in research settings to characterize plasma concentrations under controlled conditions.1,4

Nonclinical models have reported rapid systemic clearance of ALA along with metabolic processing in multiple tissues. These experimental findings are used to describe the compound’s disposition and biotransformation pathways.1,4 Published pharmacokinetic literature describing the elimination half-life of intravenous alpha-lipoic acid in humans is limited, and formal half-life values are not well established.

5. HISTORICAL AND INVESTIGATIONAL CONTEXT

Lipoic acid injections have been described historically in the literature as part of the management approach for severe mushroom poisoning, administered alongside supportive medical care.4,14 Intravenous formulations of lipoic acid have also been used in research and clinical settings in Germany and other European countries, where the compound has been investigated for various potential applications.

5.1 Research in Metabolic and Neurological Contexts

Several published studies have examined intravenous ALA in the context of metabolic and neurological research questions. These investigations have evaluated biochemical, electrophysiological, and symptom-related endpoints to explore ALA’s redox-associated activity in specific study populations.1–2

Among neurological conditions, diabetic neuropathy has been one of the most frequently studied areas. Some clinical trials have reported improvements in neuropathy-related measures such as pain, burning, tingling, or numbness compared with baseline or placebo, although findings have varied across studies.2,12 These trials were designed to examine whether modulation of redox pathways could influence neuropathy-related parameters under controlled research conditions.

5.2 Research in Hepatic and Oxidative Models

Nonclinical and early exploratory clinical studies have assessed ALA within models of hepatic and oxidative biology. These investigations have examined how ALA participates in mitochondrial dehydrogenase complexes, its role in β-oxidation–linked redox cycles, and its interactions with glutathione-dependent antioxidant systems.4-5,14 Experimental findings have described ALA-related changes in intracellular thiol status, modulation of lipid peroxidation markers, and effects on hepatic enzyme redox couples under controlled laboratory conditions.

Additional nonclinical studies have evaluated ALA in models of oxidative injury, where investigators have characterized shifts in oxidative stress biomarkers, mitochondrial redox potential, and the behavior of ALA/DHLA within hepatocellular pathways.4,14

5.3 Research in Neurobiological and Inflammatory Pathways

Nonclinical studies and preliminary human investigations have explored ALA in the context of neurobiological and inflammatory processes. These studies have examined potential effects on oxidative stress pathways, including observations related to cytokine modulation and mitochondrial function.2 Experimental models have also evaluated ALA’s influence on neuronal redox balance, intracellular thiol systems, and markers of lipid and protein oxidation under controlled conditions.

Additional research has characterized ALA’s interactions with glial and neuronal cells in oxidative or inflammatory environments, including assessments of mitochondrial enzyme activity, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and redox-sensitive signaling pathways.² Preliminary clinical studies have incorporated similar mechanistic endpoints—such as oxidative stress biomarkers and electrophysiological measurements—to explore how modulation of redox systems may relate to neurobiological parameters.

6. SAFETY PROFILE AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

Clinical studies and meta-analyses have reported that intravenous ALA is generally well tolerated at the doses and durations evaluated in those research settings. Reported adverse events primarily reflect dose-dependent or infusion-related effects and include:

-

Mild to moderate gastrointestinal, including diarrhea, nausea,

heartburn, abdominal discomfort.3,5–7,17–18

-

Odiferous urine, a benign and transient observation.17

-

Headache, dizziness, or fatigue3,6–7,18

-

Cutaneous reactions, including rash, pruritus, or urticaria.3,6–7,17–18

-

Transient hypoglycemic episodes, most commonly reported in individuals with diabetes.7,18

-

Hepatic effects, including transient elevations in liver enzymes

in clinical studies and, at excessively high doses in nonclinical studies,

evidence of acute hepatic injury.4

-

Systemic allergic reactions, including rare reports of anaphylaxis.6,17–18

-

Cardiovascular symptoms, such as palpitations, tachycardia,

and, very rarely, arrhythmias.5–6,10,18

-

Insulin autoimmune syndrome, a rare immune-mediated hypoglycemia.16–17

Reported adverse events should be interpreted within the context of study design, population, dose, and duration, and should prompt evaluation of dosing, infusion rate, and concomitant medications as appropriate.

7. FORMULATION, STABILITY, AND HANDLING

ALA is sensitive to light and should be stored in light-protected containers to minimize degradation. Experimental studies have shown that ALA can undergo reduction to dihydrolipoic acid and oxidative transformations under unfavorable storage conditions, emphasizing the need for protection from light and oxygen during preparation and handling.14

Published reports describe the use of ALA in dextrose-containing solutions14 and isotonic normal saline2 under specific experimental or clinical conditions. Comprehensive compatibility data with other parenteral drugs or diluents have not been established, and admixtures should be assessed visually for potential chemical incompatibility, discoloration, or precipitation.

Preservative-free formulations of ALA do not contain antimicrobial agents and are intended for single-use administration.

8. REGULATORY AND QUALITY CONSIDERATIONS

Outsourced sterile preparations must comply with applicable federal and state requirements, including adherence to current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) standards for FDA-registered outsourcing facilities under section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. These requirements include robust control of raw materials, manufacturing processes, aseptic practices, and finished-product testing to help ensure the quality and integrity of compounded sterile preparations.

When preparing sterile formulations, regulatory expectations generally include the use of high-quality active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) sourced from qualified suppliers, with appropriate testing and verification of identity, purity, and quality. Certificates of analysis (COAs), supplier qualification records, and confirmatory laboratory testing are commonly used to meet these expectations. APIs and excipients must also meet applicable pharmacopeial standards where available.

Process controls such as validated sterilization or aseptic filling procedures, environmental monitoring programs, and routine equipment qualification are central components of cGMP compliance for sterile compounding. Batch-specific release testing typically includes sterility testing, endotoxin testing, particulate matter assessment, and, when applicable, pH, assay, and visual inspection.

Because alpha-lipoic acid injection is not an FDA-approved drug product, compounded formulations cannot make therapeutic claims, and all preparation and distribution must occur within the regulatory framework governing 503B outsourcing facilities. Documentation practices, deviation management, and quality assurance oversight help maintain traceability and ensure that 503B products meet established internal specifications prior to release.

9. SUMMARY

Injectable ALA is not an FDA-approved drug product; however, it has been evaluated in experimental and investigational settings to characterize its pharmacokinetic behavior, including distribution and metabolism following intravenous administration. ALA has also been examined for its biochemical properties, particularly its participation in redox cycling and oxidative pathways, which has led to continued interest in research contexts involving oxidative stress and metabolic dysfunction.

Reported safety observations from published studies indicate that intravenous ALA has generally been well tolerated under the specific doses and conditions studied, although adverse events have been documented and can vary depending on dose, patient characteristics, and study design. Nonclinical studies have further explored ALA’s behavior within hepatic, neurological, and oxidative injury models, contributing to a broader understanding of its biochemical and mechanistic profile.

In summary, while ALA has been investigated across a range of experimental applications, current evidence remains preliminary. Additional well-designed, placebo-controlled clinical trials would be required to more fully characterize its pharmacokinetics, safety profile, and potential clinical relevance in human subjects.

10. SELECTED REFERENCES

-

Shay KP, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a dietary supplement: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790(10):1149-1160. [PMC2764346]

-

Ziegler D, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid in the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy: a three-week multicentre randomized controlled trial (ALADIN Study). Diabetologia. 1995 Dec;38(12):1425-33. doi: 10.1007/BF00400603.

-

Fogacci F, et al. Safety Evaluation of α-Lipoic Acid Supplementation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Studies. Antioxidants. 2020 Oct;9(10):1011. doi: 10.3390/antiox9101011.

-

Vigil M, et al. Adverse Effects of High Doses of Intravenous Alpha Lipoic Acid on Liver Mitochondria. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014 Jan;(3)1:25-27.

-

Nguyen H, et al. Alpha-Lipoic Acid. StatPearls [Internet]. NCBI Bookshelf, 2024 Jan.

-

Gatti M, et al. Assessment of adverse reactions to α lipoic acid containing dietary supplements through spontaneous reporting systems. Clinical Nutrition. 2021 Mar;40(3):1176-85. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.07.028.

-

Derosa G, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Alpha Lipoic Acid During 4 Years of Observation: A Retrospective Clinical Trial in Healthy Subjects in Primary Prevention. Drug Des, Devel Ther. 2020 Dec;14:5367-74. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S280802.

-

Han JS, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Intratympanic Alpha-Lipoic Acid Injection in a Mouse Model of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Antioxidants. 2022 Jul;11(8):1423. doi: 10.3390/antiox11081423.

-

Superti F, et al. Alpha Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants, 2024 Oct;13(10):1228. doi: 10.3390/antiox13101228.

-

Ziegler D, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Antioxidant Treatment with Alpha Lipoic Acid over 4 Years in Diabetic Polyneuropathy, The NATHAN 1 Trial. Diabetes Care. 2011 Sep;34(9):2054-60. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0503.

-

Salehi B, et al. Insights on the Use of α-Lipoic Acid for Therapeutic Purposes. Biomolecules. 2019 Aug;9(8):356. doi: 10.3390/biom9080356.

-

Yoon S, et al. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Summary Report. University of Maryland Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (M-CERSI), University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. Feb 2020.

-

Carnib BL, et al. Therapeutic applications of alpha-lipoic acid: A review of clinical and pre-clinical evidence (1998 – 2024). Biomed & Pharmacother. 2025 Oct;191:118480. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2025.118480.

-

Becker CE, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Amanita Phalloides-Type Mushroom Poisoning, Use of Thioctic Acid. West J Med. 1976 Aug;125(2):100-109.

-

Veltroni A, et al. Autoimmune Hypoglycaemia caused by oral Alpha Lipoic Acid: a rare condition in Caucasian patients. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2018 Dec;2018:18-0011. doi: 10.1530/EDM-18-0011.

-

Gomes MB, Negrato CA. Alpha-lipoic acid as a pleiotropic compound with potential therapeutic use in diabetes and other chronic diseases. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014 Jul 28;6(1):80. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-80. PMID: 25104975; PMCID: PMC4124142.

-

Natural Medicines. (2025). Alpha-lipoic acid. Therapeutic Research Center. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from ttps://fco.factsandcomparisons.com.

-

Berkson B. The Alpha Lipoic Acid Breakthrough. New York: Harmony Books; 1998.

Copyright © 2025 McGuff Outsourcing Solutions. All rights reserved.

No part of this document may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or electronic transmission, without the prior written permission of McGuff Outsourcing Solutions.